I’ve been spending some time recently thinking about the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), as well as the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) which provides a computationally efficient means of calculating the DFT of a signal.

The DFT is defined as follows. Given a discrete-time sequence x[n] where n = 0,1,2,….,N-1

Euler’s formula tells us that

Therefore, we can rewrite the DFT summation as separate expressions for the real and imaginary part of X[k] as follows (assuming x[n] is real).

where

and

As part of my thought process, I’ve been sketching out different implementations of the DFT and FFT in C and MATLAB/Octave. This one struck me as particularly nice because it’s a very plain and simple DFT by brute force.

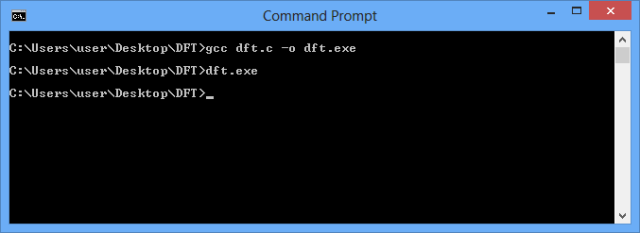

// // dft.c - Simple brute force DFT // Written by Ted Burke // Last updated 7-12-2013 // // To compile: // gcc dft.c -o dft.exe // // To run: // dft.exe // #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <math.h> #define N 16 #define PI2 6.2832 int main() { // time and frequency domain data arrays int n, k; // indices for time and frequency domains float x[N]; // discrete-time signal, x float Xre[N], Xim[N]; // DFT of x (real and imaginary parts) float P[N]; // power spectrum of x // Generate random discrete-time signal x in range (-1,+1) srand(time(0)); for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) x[n] = ((2.0 * rand()) / RAND_MAX) - 1.0; // Calculate DFT of x using brute force for (k=0 ; k<N ; ++k) { // Real part of X[k] Xre[k] = 0; for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) Xre[k] += x[n] * cos(n * k * PI2 / N); // Imaginary part of X[k] Xim[k] = 0; for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) Xim[k] -= x[n] * sin(n * k * PI2 / N); // Power at kth frequency bin P[k] = Xre[k]*Xre[k] + Xim[k]*Xim[k]; } // Output results to MATLAB / Octave M-file for plotting FILE *f = fopen("dftplots.m", "w"); fprintf(f, "n = [0:%d];\n", N-1); fprintf(f, "x = [ "); for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) fprintf(f, "%f ", x[n]); fprintf(f, "];\n"); fprintf(f, "Xre = [ "); for (k=0 ; k<N ; ++k) fprintf(f, "%f ", Xre[k]); fprintf(f, "];\n"); fprintf(f, "Xim = [ "); for (k=0 ; k<N ; ++k) fprintf(f, "%f ", Xim[k]); fprintf(f, "];\n"); fprintf(f, "P = [ "); for (k=0 ; k<N ; ++k) fprintf(f, "%f ", P[k]); fprintf(f, "];\n"); fprintf(f, "subplot(3,1,1)\nplot(n,x)\n"); fprintf(f, "xlim([0 %d])\n", N-1); fprintf(f, "subplot(3,1,2)\nplot(n,Xre,n,Xim)\n"); fprintf(f, "xlim([0 %d])\n", N-1); fprintf(f, "subplot(3,1,3)\nstem(n,P)\n"); fprintf(f, "xlim([0 %d])\n", N-1); fclose(f); // exit normally return 0; }To compile and run the above code, do the following:

When you run the executable file dft.exe, it writes an M-file called dftplots.m which can then be run in MATLAB or Octave to produce plots of the results. This is the M-file produced by dft.exe:

n = [0:15]; x = [ 0.672957 -0.453061 -0.835088 0.980334 0.972232 0.640295 0.791619 -0.042803 0.282745 0.153629 0.939992 0.588169 0.189058 0.461301 -0.667901 -0.314791 ]; Xre = [ 4.358686 -2.627209 -2.558252 2.144204 1.888348 3.210599 2.147089 -1.166725 0.332542 -1.166852 2.146972 3.210663 1.888432 2.144283 -2.558007 -2.627225 ]; Xim = [ 0.000000 -0.959613 -0.352430 1.534066 0.408726 -0.478590 -0.390162 0.160532 0.000022 -0.160326 0.389984 0.478336 -0.408804 -1.534269 0.352723 0.959997 ]; P = [ 18.998148 7.823084 6.668859 6.950971 3.732913 10.536995 4.762218 1.387017 0.110584 1.387247 4.761577 10.537162 3.733295 6.951930 6.667812 7.823905 ]; subplot(3,1,1) plot(n,x) xlim([0 15]) subplot(3,1,2) plot(n,Xre,n,Xim) xlim([0 15]) subplot(3,1,3) stem(n,P) xlim([0 15])I ran dftplots.m in Octave, as shown below:

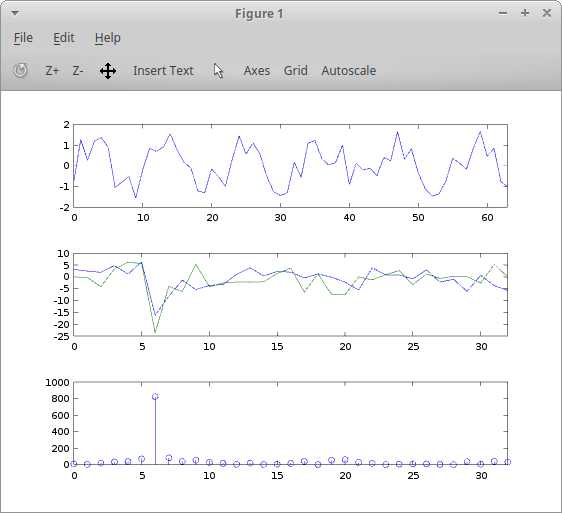

It produced the following graphs:

The top plot is the original random discrete-time sequence x[n]. The second plot shows the real and imaginary parts of X[k]. Note the symmetry of X[k], which is just as we expect for real x[n]. The final plot is P[k], the power spectrum of x[n]. Basically, each value of P[k] is the square of the magnitude of the corresponding complex value X[k]. Again the symmetry is just as we expect for real x[n].

As a follow up to the above example, I modified the program a little to perform the DFT somewhat more efficiently and to transform a longer (64-sample) frame of data. I also modified the random time domain signal generation process a bit to add a dominant frequency component (at k=5.7, i.e. between bins 5 and 6).

This is the modified C code:

// // dft2.c - Basic, but slightly more efficient DFT // Written by Ted Burke // Last updated 10-12-2013 // // To compile: // gcc dft2.c -o dft2.exe // // To run: // dft2.exe // #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <math.h> // N is assumed to be greater than 4 and a power of 2 #define N 64 #define PI2 6.2832 // Twiddle factors (64th roots of unity) const float W[] = { 1.00000, 0.99518, 0.98079, 0.95694, 0.92388, 0.88192, 0.83147, 0.77301, 0.70711, 0.63439, 0.55557, 0.47139, 0.38268, 0.29028, 0.19509, 0.09801, -0.00000,-0.09802,-0.19509,-0.29029,-0.38269,-0.47140,-0.55557,-0.63440, -0.70711,-0.77301,-0.83147,-0.88192,-0.92388,-0.95694,-0.98079,-0.99519, -1.00000,-0.99518,-0.98078,-0.95694,-0.92388,-0.88192,-0.83146,-0.77300, -0.70710,-0.63439,-0.55556,-0.47139,-0.38267,-0.29027,-0.19508,-0.09801, 0.00001, 0.09803, 0.19510, 0.29030, 0.38269, 0.47141, 0.55558, 0.63440, 0.70712, 0.77302, 0.83148, 0.88193, 0.92388, 0.95694, 0.98079, 0.99519 }; int main() { // time and frequency domain data arrays int n, k; // time and frequency domain indices float x[N]; // discrete-time signal, x float Xre[N/2+1], Xim[N/2+1]; // DFT of x (real and imaginary parts) float P[N/2+1]; // power spectrum of x // Generate random discrete-time signal x in range (-1,+1) srand(time(0)); for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) x[n] = ((2.0 * rand()) / RAND_MAX) - 1.0 + sin(PI2 * n * 5.7 / N); // Calculate DFT and power spectrum up to Nyquist frequency int to_sin = 3*N/4; // index offset for sin int a, b; for (k=0 ; k<=N/2 ; ++k) { Xre[k] = 0; Xim[k] = 0; a = 0; b = to_sin; for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) { Xre[k] += x[n] * W[a%N]; Xim[k] -= x[n] * W[b%N]; a += k; b += k; } P[k] = Xre[k]*Xre[k] + Xim[k]*Xim[k]; } // Output results to MATLAB / Octave M-file for plotting FILE *f = fopen("dftplots.m", "w"); fprintf(f, "n = [0:%d];\n", N-1); fprintf(f, "x = [ "); for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) fprintf(f, "%f ", x[n]); fprintf(f, "];\n"); fprintf(f, "Xre = [ "); for (k=0 ; k<=N/2 ; ++k) fprintf(f, "%f ", Xre[k]); fprintf(f, "];\n"); fprintf(f, "Xim = [ "); for (k=0 ; k<=N/2 ; ++k) fprintf(f, "%f ", Xim[k]); fprintf(f, "];\n"); fprintf(f, "P = [ "); for (k=0 ; k<=N/2 ; ++k) fprintf(f, "%f ", P[k]); fprintf(f, "];\n"); fprintf(f, "subplot(3,1,1)\nplot(n,x)\n"); fprintf(f, "xlim([0 %d])\n", N-1); fprintf(f, "subplot(3,1,2)\nplot([0:%d],Xre,[0:%d],Xim)\n", N/2, N/2); fprintf(f, "xlim([0 %d])\n", N/2); fprintf(f, "subplot(3,1,3)\nstem([0:%d],P)\n", N/2); fprintf(f, "xlim([0 %d])\n", N/2); fclose(f); // exit normally return 0; }When I ran the resulting M-file in Octave, the following graphs were produced:

The dominant frequency component introduced into the random signal results in the single prominent peak in the above graph.

By the way, I generated the values for the global array of twiddle factors in the above example using the following short C program (which runs on the PC rather than the dsPIC):

// // twiddle.c - Print array of twiddle factors // Written by Ted Burke // Last updated 10-12-2013 // // To compile: // gcc twiddle.c -o twiddle.exe // // To run: // twiddle.exe // #include <stdio.h> #include <math.h> #define N 64 int main() { int n; for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) { printf("%8.5lf", cos(n*6.2832/N)); if (n<N-1) printf(","); if ((n+1)%8==0) printf("\n"); } return 0; }

Ted, this looks great. I’ll go over in more detail later

Reblogged this on richardsdspblog and commented:

Check this out

please put some sketches of DFT how it works inside dspic30f4011 to understand better

because i am beginner of c30 with mplab. and suggest me that which is good mplab 8 or mplab x

Hi Karthik,

Sorry, but I don’t have time to provide a detailed explanation of the how the DFT works, but it’s no different in the dsPIC than it is anywhere else, so there are many excellent explanations available online and in textbooks. The only thing that’s unusual about the DFT implementation I presented here is that it doesn’t use the so-called Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), which most implementations do (with good reason – it’s way more efficient for transforming long sequences). However, even though I didn’t use the FFT here, it’s still exactly the same old DFT that’s being calculated. The FFT is just a fast method of computing the DFT. Whether you use the FFT or not to calculate the DFT, for a given time-domain sequence, it’s still the same set of complex numbers you end with.

My implementation directly calculates each DFT sample using the classic textbook summation (for example, see equation 1 in the Wikipedia DFT article). This is the part of my code that computes the DFT samples (and also calculates the power in each DFT bin):

// Calculate DFT of x using brute force for (k=0 ; k<N ; ++k) { // Real part of X[k] Xre[k] = 0; for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) Xre[k] += x[n] * cos(n * k * PI2 / N); // Imaginary part of X[k] Xim[k] = 0; for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) Xim[k] -= x[n] * sin(n * k * PI2 / N); // Power at kth frequency bin P[k] = Xre[k]*Xre[k] + Xim[k]*Xim[k]; }The input discrete-time sequence is the array X[] which contains N samples. The output of the DFT is a list of N complex values. The real parts are stored in the array Xre[] and the imaginary parts are stored in Xim[]. The power in each bin is just the square of the magnitude of the complex value. These power values are stored in the array P[], which therefore also contains N elements.

Regarding MPLAB 8 versus MPLAB X:

Although I have had many problems with MPLAB X (compared to MPLAB 8) I would still recommend using that if you are going to use one or the other. MPLAB 8 is being phased out, so you are likely to find it supported less and less over time. Conversely, MPLAB X will hopefully improve over time.

I actually don’t use MPLAB at all myself anymore (although some of my students do). I just use a text editor and the XC16 C compiler (which is the same compiler MPLAB X uses for the dsPIC). To transfer my compiled hex files onto the microcontroller, I use the PICkit 2 software utility (I use a PICkit 2 USB programmer). If you’re using a PICkit 3 or something else, I think there’s another programming software utility that comes with MPLAB X, but I haven’t tried it.

Ted

Hello, can you help me, providing me the reference for obtain twiddle factors?. Sorry, I don’t know that part. Thank.

Hi Raul,

The so-called twiddle factors used in the FFT are just complex roots of 1. Specifically, in the above example a 64-point DFT is being performed, so the twiddle factors are the 64-th roots of 1 – i.e. 64 complex values distributed evenly around the unit circle (in the complex plane). Each of these values, when raised to the power of 64, is equal to 1. Naturally, one of the values is the number 1 itself since 1^64 = 1. The remaining 63 values are spread evenly around the unit circle.

These values are used very extensively in the well-known Cooley-Tukey FFT algorithm. They could be calculated on the fly using sin and cos function calls (see Euler’s formula: e^jx = cos(x) + j.sin(x) ). However, since the same values are used over and over again, you can save a lot of computing time by pre-calculating them.

In the above example, the twiddle factors are stored in an array called W. Clearly, the values in the array are real rather than complex. These 64 values are cosines of angles evenly spaced between 0 and 2*pi radians. Because of the trigonometric identity, sin(x) = cos(x + pi/2), you can use the same array of values to obtain sines of the same angles simply by applying an offset to the array index.

You can read more about twiddle factors here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cooley%E2%80%93Tukey_FFT_algorithm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fast_Fourier_transform

Hope that helps!

Ted

Thank you very much for your help, really helped me.

Thanks Raul, I’m glad you found it useful.

Ted

Hello,

I used your example of dft for a presentation in a course of dsp (elective master) because of the C implementation. Thank you for providing your knowledge!

Thanks Mauricio – I’m delighted you found this useful. Best of luck with your adventures in DSP. When I was doing my masters back in the 1990s, I spent a lot of time trying to develop a thorough understand of the DFT. That thought process turned out to unlock many other fundamental concepts in DSP – correlation, orthogonal basis functions, Z-transform, etc. For me, understanding this one transform really marked the beginning of a life-long passion for DSP.

Ted

fuck you ted your DFT’s are bullshit, although if your interested in a chat, maybe we can meet up as well ?

Best of wishes, lots of love,

John Mayo

Lover of Mayo

Grammar

hi. i need help with a 16 point dft implementation where the input values are to be given :

input = [1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

please help me out.

and i need assembly code ( ARM simulator)

If you can write the c code , i will convert it to arm code somehow.

please let me know

Sounds like his class assignment is late 🙂

I was using FFT in the ARM CMSIS linrary for FFT and wondered if there was something faster, so i compiled your code only to find out its about 5X clower… that is not to say you code is bad, but rather to say most likely the ARM CMSIS library is hand written and optimized in assembler 🙂 But I do rather like looking at the C code as it simply shows you how its calculated.

RichardS

Hi Richard,

Ha ha, the above code certainly won’t be fast! Although it calculates the exact same thing as the FFT (i.e. the Discrete Fourier Transform or DFT), it does so through brute force summation for each frequency bin rather than using the elegant (but harder to understand) approach of the FFT algorithm. For short window lengths the cost of doing the DFT summation directly isn’t too awful, but as window length increases the greater efficiency of the FFT becomes more and more significant.

If you’re looking for a fast FFT library, maybe try FFTW? As far as I recall, it’s open source and pretty quick to get up and running with.

Ted

Hello Ted,

Maybe I miss something, but looking to the Figure 1 does not correspond to the data (m file) shown above.

Hi Ponzifex,

Well spotted! The C code generates a new random discrete time signal each time it runs, so I think what happened was that I mixed up the M-file from one trial with the signal plots from another. Anyway, I think I’ve fixed it so hopefully everything is consistent now.

Thanks,

Ted

Cool, thanks for the quick fix.

One more thing, I would like to make similar stuff: https://youtu.be/QVuU2YCwHjw using Fourier series.

Do I have to feed the coordinates of the shape to the Fourier transfer like this?

float angle = n * k * PI2 / N;

Xre[k] += point[n].x() * cos(angle) + point[n].y() * sin(angle);

Xim[k] += point[n].y() * cos(angle) – point[n].x() * sin(angle);

float magnitude = sqrt(Xre[k]*Xre[k] + Xim[k]*Xim[k]);

float phase = atan2(Xim[k], Xre[k]);

After the Fourier transform, can I use the magnitude, phase and the frequency to construct these epicycles?

Ha ha, that’s an interesting video!

To do something like the example in the video, I think you’ll need to adapt the above code quite a bit. If I’m understanding the underlying principle correctly, then each sample in your input array will be a complex number that represents a point on the curve you’re trying to draw. The example above assumes real values in the time domain (the input array), which results in complex conjugate symmetry between the top and bottom halves of the output array. I therefore only calculated frequency domain values up to the Nyquist frequency (half of the full spectrum). However, if your input values are not real, you need to calculate the entire frequency spectrum because the symmetry won’t be present any more.

Since both input and output arrays are complex, I would strongly suggest using the complex library functions in the C standard library since it will simplify the code significantly.

Here’s a rough sketch of the sort of thing you could use:

// // dft.c - DFT example // Written by Ted Burke - 5-1-2017 // // To compile: // gcc dft.c -o dft.exe -lm // // To run: // dft.exe // // To load and plot the resulting magnitude spectrum in Octave: // data = csvread('data.csv'); // plot(data(:,1), data(:,2)) // #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <math.h> #include <complex.h> #include <time.h> // just for seeding random number generation // N is assumed to be greater than 4 and a power of 2 #define N 64 int main() { // Time and frequency domain data arrays int n, k; // time and frequency domain indices complex double x[N]; // complex-valued discrete-time signal complex double X[N]; // complex-valued frequency-domain samples double P[N]; // power spectrum // Create W array containing the complex Nth roots of 1 complex double W[N]; for (k=0 ; k<N ; ++k) W[k] = cexp(I*k*2*M_PI/N); // Load discrete-time samples into x srand(time(0)); for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) { // N.B. I'm just filling x[] with a noisy sin wave! x[n] = sin(5.7 * n * 2.0 * M_PI / N); x[n] += -1.0 + ((2.0 * rand()) / RAND_MAX); } // Calculate DFT samples (no FFT here - just brute force summation) for (k=0 ; k<N ; ++k) { X[k] = 0; for (n=0 ; n<N ; ++n) X[k] += x[n] * W[(n*k)%N]; } // Write output to file FILE *f = fopen("data.csv", "w"); double normfreq, magnitude, phase; for (k=0 ; k<N ; ++k) { normfreq = k*2.0*M_PI/N; magnitude = cabs(X[k]); phase = atan2(cimag(X[k]), creal(X[k])); fprintf(f, "%lf,%lf,%lf\n", normfreq, magnitude, phase); } fclose(f); // exit normally return 0; }Instead of filling x[ ] with a noisy sin wave as I did above (just for some convenient data), you’ll need to fill it with complex numbers that mark the points on the curve you want to trace out. The resulting CSV (comma separated values) file contains three columns of data. The first column is normalised frequency (in radians per sample, I think). The second column contains magnitude. The third column contains phase (in radians). As I understand it, that’s the information you need to create your animation, although of course getting from the values to a working animation will take some work!

Ted

I have figured out what is going on with the negative frequencies. Here is what I made:

8 sample points (coordinates) represented as complex numbers and made Fourier transform on them. I had to set up the epicycles like half of them spinning in CW and the other half spinning CCW. Here is the result: https://youtu.be/URrmr8CVDDg

You may want to delete my previous post since it may be misleading and I look like a complete fool 😀

Thanks!

That’s pretty cool Ponzifex!!

Since your last comment, I have give some further thought to this. This type of animation is actually a very interesting way of visualizing the discrete Fourier transform.

As I’m currently picturing this, it does seem like fitting the motion to a large number of points will also require a large number of epicycles. Watching the original Homer Simpson version, it looks like there are more points on the curve than there are epicycles, but it’s hard to be sure. Presumably, you used 8 epicycles to fit your 8 points? I’ve been trying to figure out if there’s a way to do it with less epicycles, for example by splitting the points into smaller groups and changing the speed of rotation of each epicycle as the animation moves from one group to the next. It’s not quite as simple as that, of course, but it’s an intriguing challenge.

By the way, the curved wavy path in between points (rather than straight lines) is exactly what I would expect from the DFT. The inverse DFT (which is more or less what you get when you use your DFT samples as the parameters of your epicycle system) only guarantees to hit the original sample values at uniform intervals in time. In between those sampling times, the signal does “whatever it needs to” to arrive at the next sample value exactly on time.

Finally, as I understand it, the fact that you got things working by reversing the direction of some of the epicycles is an example of “aliasing”. In some senses, each frequency bin in the DFT is “equivalent” (ok, I’m on thin ice here) to other bins that are separated from it by an integer multiple of the sampling frequency. For example, in your animation it looks like it hits a sample value every 1.5 seconds. Therefore, we can say that the sampling frequency Fs = 1 / 1.5 = 0.6666 Hz. Your 8 epicycles have the following respective frequencies:

f0 = 0 x 0.6666 / 8 = 0.00000 Hz

f1 = 1 x 0.6666 / 8 = 0.08325 Hz

f2 = 2 x 0.6666 / 8 = 0.16650 Hz

f3 = 3 x 0.6666 / 8 = 0.24975 Hz

f4 = 4 x 0.6666 / 8 = 0.33333 Hz

f5 = 5 x 0.6666 / 8 = 0.41625 Hz

f6 = 6 x 0.6666 / 8 = 0.50000 Hz

f7 = 7 x 0.6666 / 8 = 0.58275 Hz

However, for each of these there are an infinite number of higher or lower frequency epicycles (including negative frequency epicycles) that can be substituted while still hitting the original sample values. For example, consider the epicycle at f6 (0.5 Hz). That epicycle can be replaced by one with a frequency of 0.5 + 0.666 = 1.166 Hz or by one with a frequency of 0.5 – 0.666 = -0.166 Hz. In the latter case, the negative frequency just means the epicycle rotates in the opposite direction.

Ted

Hello Ted,

Yes, I have used 8 epicycles for 8 sample points. In some cases when the data points are symmetrical like the corner points of a square which means 4 sample points and only 2 epicycles are required. I have played with my example a bit and noticed if I remove epicycles with low amplitudes the resulting curve won’t hit the sample points but goes beside them closely. Earlier I have found this smart guy’s article about Fourier series: http://iquilezles.org/www/articles/fourier/fourier.htm

By removing coefficients means you loose details, but the big picture is still visible.

Here are the Fourier coefficients that I got in my example and a little explanation what I consider as negative and positive frequencies. To make the animation enjoyable I have divided the freqencies by 15 to make thing happen slower.

freq bin, magnitude, phase

k0, 8.83883, -0.785398 (0Hz) <- this one is not spinning but gives an offset.

k1, 20.0026 -0.562617 (-1Hz)

k2, 12.5 0 (-2Hz)

k3, 25.341 -2.70701 (-3Hz)

k4, 19.7643 -0.32175 (4Hz)

k5, 8.28535 -0.222781 (3Hz)

k6, 17.6777 -0.785398 (2Hz)

k7, 197.994 -0.00924644 (1Hz)

For example with one more sample points there would be one more extra frequency bin (-4Hz) and so on. If I would have 0 amplitude somewhere after the Fourier transform I would drop it so it can be considered as compression 🙂

Have a good one!

Hello Ted,

I have finished my app that demonstrates Fourier transform, please take a look: https://youtu.be/_wKpKePKoDg

That’s brilliant Ponzifex!! Very impressive and quite thought-provoking.

I’m curious about the effect of spacing the sample points differently. I think you described them as uniformly spaced in time (which of course they are), but they also seem to be evenly spaced along the length of the curve. I wonder if it would be better to vary the spacing according to the curvature of the line – i.e. put them closer together where the curve bends sharply and farther apart where the curve bends very gently. Viewed as a function of time, that would probably help to “smooth out” the sharp corners that are harder for the sinusoidal basis functions to fit correctly.

Anyway, thanks again for sharing this. I’d love to try my hand at doing this myself. It’s a great way of visualising the DFT.

Ted

I don’t know your email address, so I uploaded the c++ code to my dropbox: https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/68813132/fouriergl.zip

I can provide binary too, just mail me if you need it.

Hi,

I think you made a mistake.

Xre[k] = …. *cos(k2n(pi)/N)

and not Xre[k] = …. *cos(j * 2n(pi)/N).

The same occurs for Xim[k].

Hi Larissa,

Sorry, but I can’t really see what you mean. Are you talking about lines 37 and 41? They seem correct to me.

Ted

Aha! Now I see what you’re talking about. I was looking at the code rather than the equations. Well spotted! I’ll fix that now.

Ted

Sorry, but I can’t really see what you mean. Are you talking about lines 37 and 41? They seem correct to me.—>

I don’t what happened!

Can you show modified code.

Thanks

Aaron

Hi Aaron,

There was no change to the code – that was just my misunderstanding Larissa’s original comment. What she actually spotted was a typo in the mathematical equation I had shown (i.e. the mathematically typeset equation rather than the code). The code was and remains correct. The equation is fixed now too.

Ted

Can you please give me some code?

I want to use it as a learning

My e-mail:ktr66636@gmail.com

This one is gold, thank you for implementing.

Pingback: Twiddle-factor FFT for microcontrollers | Łukasz Podkalicki

Glad I found your little page here. I’m interested in a simple DFT implementation (in assembly language, my preference), and your code and explanation finally give me what I need to get started.

I’m calling my project “SDFTW”, the Slowest DFT in the West, as opposed to the FFTW, the Fastest Fourier Transform in the West. (Speed may or may not come later; for now I’m just interested in proof of concept.)

One small quibble: the transformation you gave from exponential to cosine/sine is attributable to Euler’s formula, not DeMoivre’s Theorem:

e^iθ = cosθ + i sinθ

Other than that, great stuff!

Oops, you’re absolutely right! Not sure how I managed that – I can’t even remember what de Moivre’s formula is 😀

Anyway, thanks for letting me know – it’s fixed now.

I love the sound of your SDFTW – that’s pretty much what I was going for here in C, but doing it in assembly sounds like no mean feat. Are you blogging somewhere I can see it when it’s done?

Ted

Hi, and thanks for the quick response. (Wasn’t really expecting any, since the last previous comment before mine on that page was from 2019.) Actually, I find coding in assembly language (32-bit X86, using the Win32 API) pretty easy. Using your C code as a guide, it’s almost a 1-to-1 translation. Takes more vertical space and a few more statements. Anyhow, I’ll be happy to send you my code and explanatory notes when I get to it if you like. Before I tackle the DFT I’m writing a small tool to generate a file with sine tones (multiple, so I can see if they get separated correctly) so I have a programmable source of data. When that’s done I’ll start on the SDFTW. I haven’t looked at the rest of your site: are you coding for a microcontroller? If so, sounds like fun. Some years back I did some stuff on a chip called the SX-28, then owned by Microchip, later sold to [someone else, forget who]. I’d like to try that again in the near future. I like the idea of using those small but underutilized machines. I must say I appreciate the level of writing and clear explanation on your blog. There’s a ton (tonne to you, I guess) of stuff on the web, but 90% of it is crap, even if technically correct, because the writer can’t put together a coherent sentence. I’ve been searching for just this simple explanation of the DFT for some time; what was hanging me up was looking at the exponential formula and trying to figure out how the hell to deal with “i” (sqrt(-1)). Your solution–shifting to sin/cos–was just the thing. “NoCforMe”

Thanks for your kind words Orinda. Glad you found this useful.

I do quite a bit of microcontroller programming on various platforms, mostly as part of my undergrad teaching. Currently, the micro I use most is the ATmega328 because that’s what’s in the Arduino Nano, which I use in several class projects.

Anyway, enjoy your adventures in assembly – hope you get it working!

Ted